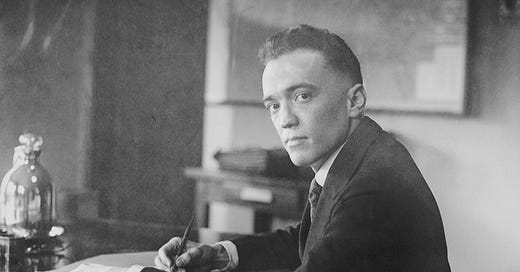

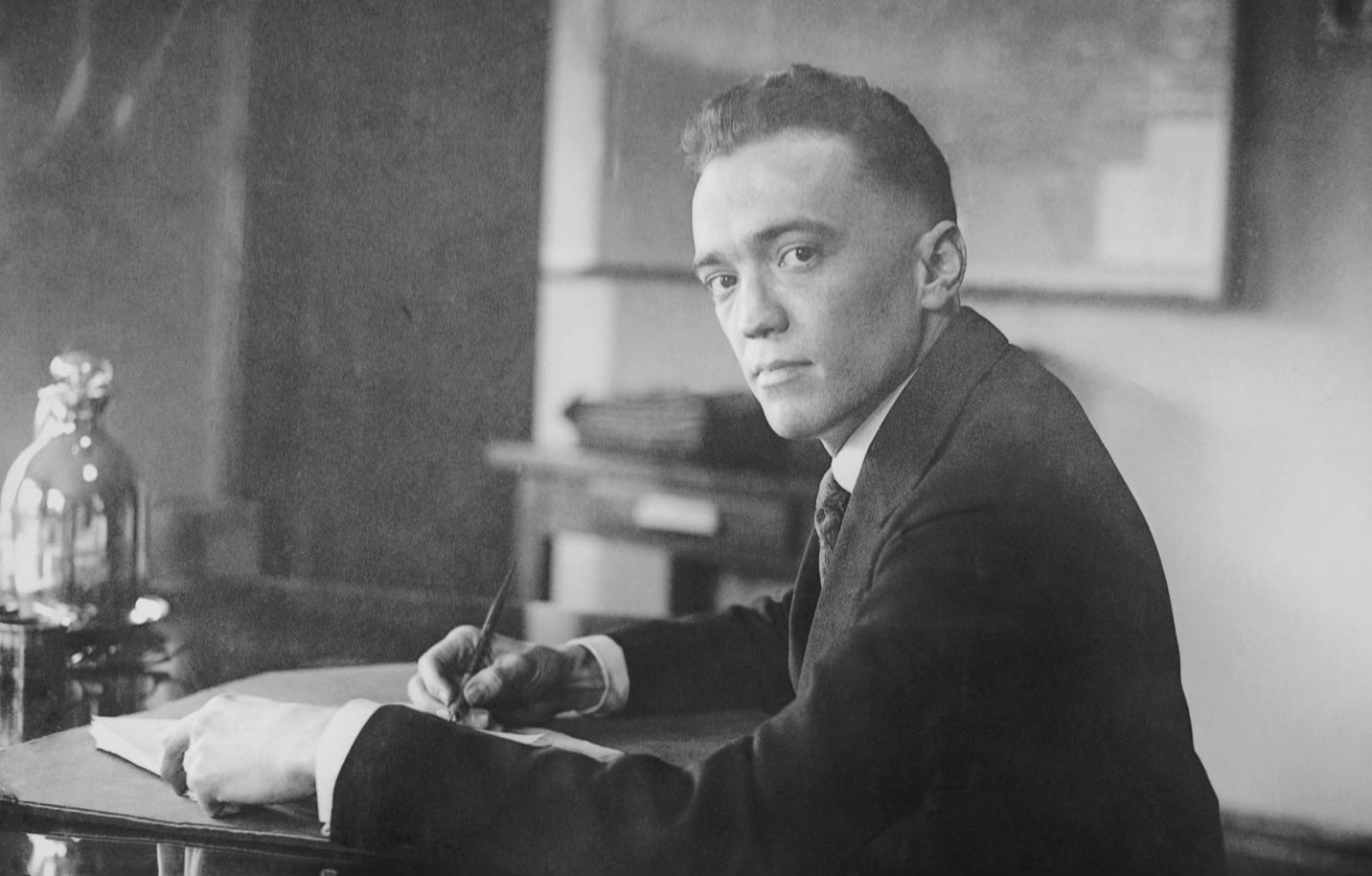

How J. Edgar Hoover, at age 23, rounded up foreign anarchists & communists

Excerpted from Big Intel: How the CIA and FBI Went from Cold War Heroes to Deep State Villains.

In 1918, Hoover earned a promotion to run the Alien Enemy Bureau to lead the fight against anarchists and Marxists. He was 23 years old. At least 6,500 German nationals sat confined in camps under his authority, with another 450,000 under some kind of monitoring.

Weeks before the Bolsheviks swept over Russia in November, 1917, and mindful of the influx of agitators from abroad, Congress amended immigration law to protect against foreign extremists wracking America.

All “aliens who disbelieve in or advocate or teach the overthrow by force or violence of the Government of the United States shall be deported,” the law said, adding that “aliens who are members of or affiliated with any organization that entertains a belief in, teaches, or advocates the overthrow by force or violence of the Government of the United States shall be deported.”

Then came the Sedition Act of 1918, which would ensnare socialist labor organizer Eugene Debs, who had shared the platform the year before with Trotsky.

The new wartime laws meant a huge amount of work at the relatively tiny Justice Department. Alien Enemy Bureau Chief Hoover immersed his life completely into the mission.

J. Edgar, hunter of Marxists and anarchists

At age 24, shortly after the Armistice of November 11, 1918, Hoover earned a promotion to head the Justice Department’s General Intelligence Division, popularly known as the Radical Division.

Its job was to hunt down extremists and others – mainly anarchists, radical socialists, and communists, both American-born and foreign-born – who sought to subvert American constitutional government. Part of the job involved collecting information from local police departments. Hoover would then draw up lists of suspected anarchists and other subversives responsible for the violence and other illegal agitation.

The Roaring Twenties had not yet arrived. Unemployment, inflation, vicious labor strikes, race riots, and terrorist bombings scarred the early postwar years. All made worse by a deadly influenza pandemic.

Terrorists mailed bombs to a US senator and the mayor of Seattle, with a New York postal worker the next day finding 18 more explosive packages bound for prominent political and business leaders. An anarchist terrorist bombed the home of Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer in May, 1919, shaking the neighbors, the young Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt. That day, coordinated attacks struck political figures, judges, and police officers in eight cities across the country.

Hoover runs deportation of enemy aliens

The public demanded action. Hoover oversaw the deportation of 249 Russia-born anarchists and Communists back to their homeland. He arranged for a recently decommissioned troop transport, the Buford, to send them all from a holding center on Ellis Island in New York Harbor to Bolshevik Russia, and brought a group of congressmen with him to watch the deportation.

One congressman described Hoover that night as “a slender bundle of high-charged electric wire.” With US soldiers on board as guards, the Buford steamed to Helsinki, where Finnish and American troops would take them across the border into Russia and hand them over to Trotsky’s Red Army.[3]

That done, Attorney General Palmer and Hoover resolved to round up even more undesirable foreigners and other domestic extremists. Hoover anticipated as many as 10,000. With the cooperation of local police, in early 1920 the Palmer Raids began to sweep up thousands of suspected subversives, deporting hundreds.

But the Palmer Raids suffered from poor planning, often inadequate or wrong intelligence, and bad communication. Problems plagued the lawmen at every turn, from issuing warrants to making arrests. Innocent people, mostly immigrants who spoke little or no English, got swept up while bad ones got away. Many Americans thought the roundups had gone too far.

Some might say that the Palmer Raids failed to go far enough. The month before, in Moscow, at about the time the Buford was making its way to Finland, the Soviet regime began organizing its machinery for international aggression. It founded its global Comintern network that would send Kremlin agents and operatives into the United States and organize radicals into disciplined Soviet assets.

ACLU is created to defend those same anarchist and communist networks

Inside the United States, the foreign enemies of the Constitution would mobilize immigrants and American citizens already predisposed toward the Bolsheviks, carefully recruiting hundreds or perhaps thousands as agents of the Red Army’s GRU military intelligence and the Cheka and its successors. Those assets would organize. They would propagandize. They would agitate. They would infiltrate. They would subvert. They would spy. And they would influence far beyond their own small cadres.

Palmer hadn’t commanded or controlled those raids. Hoover had. Faced with the backlash, Hoover learned valuable lessons and experienced how to survive every political crisis and transition.

Like a warrior monk, Hoover lived an ascetic life, wedded to the constant work of his unique mission. As a good son, he stayed at home to care for his parents, as he would until his mother died when he was age 43.

In the months after the Palmer Raids, two notable developments occurred.

First, liberal and progressive jurists founded a group called the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) to defend accused anarchists and Communists and protect their rights to agitate and subvert.

Secondly, Hoover started to become a national figure as the vanguard against extremist subversion of the United States. Now 25 years old, Hoover made his first official report to Congress under a Great War-era anti-subversion law. He presented an intensive, well-organized, carefully detailed document that showed sophistication and nuance.

Hoover told Congress that the Socialist Party in the United States, composed largely of immigrants who exported their Central European ideologies to their new home, had split. One branch advocated the Bolshevik tactics inspired by Trotsky in New York and reconstituted as the Communist Party USA.

Excerpted from my book Big Intel: How the CIA and FBI Went from Cold War Heroes to Deep State Villains (Regnery, 2024).